Translating Poetry into Song

This project endeavors to unveil the enigmatic connections that lie beneath the surface of poetry and music, exploring uncharted territories within the interplay of author-reader relationships. Zhongxing Zeng presents Eric Schlich's prose "When You Are Old and I Am Gray" from HFR Issue 59 translated into song.

Musical Translation

Song Translation by Zongxing Zeng

The Tulips (Listen on Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube)

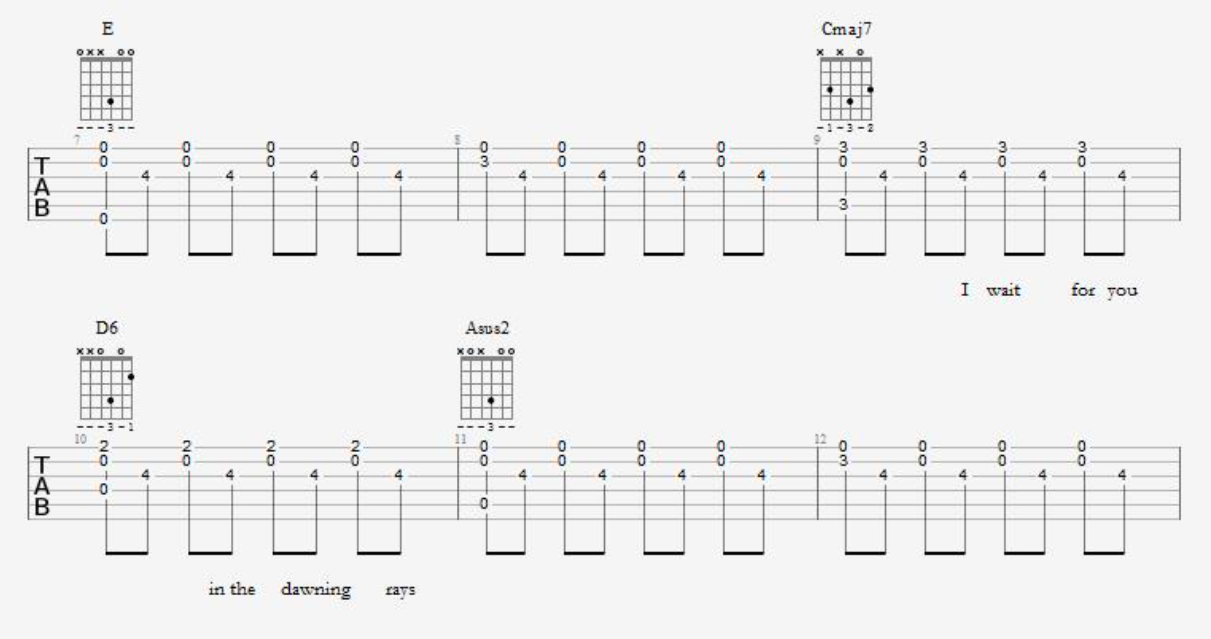

I wait for you in the dawning rays

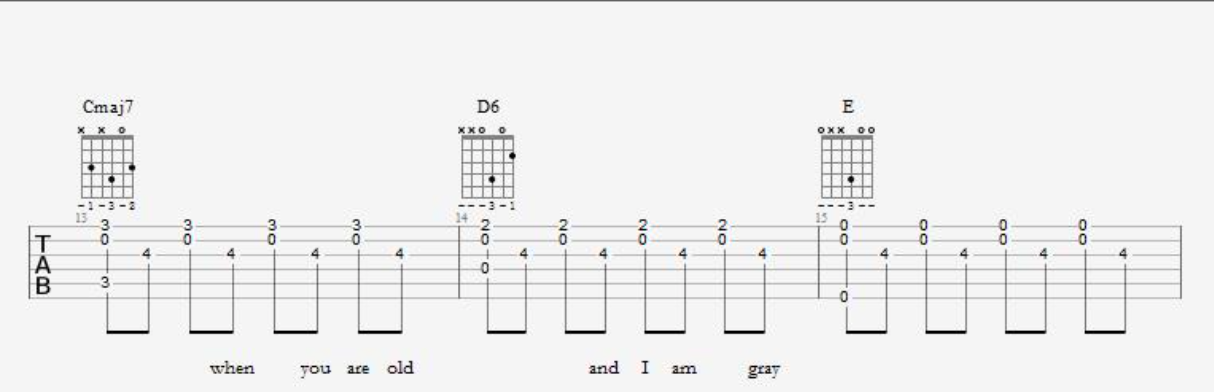

when you are old and I am gray

dying over the lip of the vase, the tulips

you said how lovely they look, their sloping grace

as if the night has lost its way to the day

as if time has stopped for them to celebrate

as if they will stay here and never fade away

Oh so long ago,

It is a time I can barely remember

a time before you

All that I need to know

is you love this flower and I love you

when you are old and I am gray

dying over the lip of the vase, the tulips

you said how lovely they look, their sloping grace

as if the night has lost its way to the day

as if time has stopped for them to celebrate

as if they will stay here and never fade away

I wait for you in the dawning rays

when you are old and I am gray

I wait for you in the dawning rays

when you are old and I am gray

Song Title: The Tulips | Words by Eric Schlich & Zhongxing Zeng | Music by Zhongxing Zeng | Full sheet music linked below:

When You Are Old and I Am Gray by Eric Schlich

The kitchen windowsill is lined with prescription bottles. I count out your pills and set them on the counter. Pour you a glass of orange juice. Put the coffee on. I can hear you in the bathroom, performing your daily beauty chores. Faucet running, dryer blowing, the clatter of makeup in the sink. On the table, there are the tulips from our anniversary. Already, their heads are too heavy for their stems. You once told me they are the loveliest of flowers to watch die. Long ago, a tulip was just a tulip. This is so long ago, it is a time I can barely remember, a time before you. Before your love for this flower spilled over into my life. This is how something simple, something in this world, something that just is, takes on meaning. I know many facts about tulips, but I will not recite them now. I can feel them elbowing each other, grasping for purchase in my head—competition for a metaphor—but really all that matters is you love this flower and I love you. Always I thought I’d keep books for company. While that is still true—they cover our mantel, they clutter our bedroom, they fill the walls, our books—it became, somehow, a lesser truth. And I am happy for it. You are making your way down the hall now, I can hear you. You will make a fuss about taking the pills, as you do every morning. You will shake your head in that way when you drink the juice. And you will sit at the table, where I will be drinking my coffee, eating my banana, reading my book. If there were a signature pose, a moment I’m most myself, it is this one: reading, but not reading, anticipating your entrance into the room, looking up from the page too soon. It is not so much that we have spent our lives in this way—our time together cannot be weighed in the currency of bananas or books or even tulips—but that after all these years, it still brings me pleasure, your comment upon entering the kitchen, on how lovely they look, there, on the table, dying over the lip of the vase: the tulips, their sloping grace.

About the Writer:

Eric Schlich is the author of Eli Harpo's Adventure to the Afterlife, a novel forthcoming from Overlook Press (January 2024) and the story collection Quantum Convention, winner of the 2018 Katherine Anne Porter Prize. His stories have appeared in American Short Fiction, Gulf Coast, and Electric Literature, among other journals. He lives in Memphis, Tennessee, where he is an assistant professor at the University of Memphis.

Project Introduction

This project delves deeply into a multifaceted, creative process, one that unfolds across three distinct realms of communication: intersemiotic, interlingual, and intralingual. Through this exploration, it navigates the intricate interplay between words and sounds, unearths the nuanced connections and demarcations between poetry and music, and identifies the delicate line between translation and adaptation. This endeavor involves deciphering both the implicit and explicit meanings embedded within verbal expressions, experimenting with the auditory attributes of poetic compositions, and orchestrating a transformation of textual messages into melodic phrases.

In his seminal 1959 article titled “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation,” Roman Jakobson posits a compelling notion: that every cognitive experience finds expression through language. He categorizes translation into three distinct dimensions: intersemiotic, interlingual, and intralingual translation. In the realm of poetry-music translation, all three categories intertwine seamlessly.

Firstly, intersemiotic translation, often termed “transmutation,” involves the interpretation and transference of words from a verbal sign system into melodies within a non-verbal sign system. This dynamic process engenders the fusion of linguistic essence with melodic form. Furthermore, the convergence of poetry and music has long been acknowledged as a universal language that resonates with all sentient beings, traversing centuries, borders, and cultures. This places poetry-music conversion firmly within the realm of interlingual translation, wherein verbal signs from one language are transposed into musical signs in another language. This bridge between spoken and musical languages connects diverse worlds through shared emotional chords. Lastly, the intrinsic oral and aural attributes that poetry and music share—such as meter, accent, duration, tempo, pitch, and tone—alongside their sonic devices like rhythm, rhyme, repetition, and more, render these two art forms harmoniously blended. This symbiosis establishes them as agents of a shared language. Consequently, the translation from poetry to music finds its place within the realm of intralingual translation, akin to rewording, where verbal signs are artfully reimagined through different signs of the same language. In embracing all three dimensions of translation, poetry-music translation transcends the mere confines of linguistic transfer, emerging as a multidimensional art that bridges the realms of language, sound, and emotion.

The art of translating poetry into music has traversed the annals of time, with countless instances spanning classical opuses to modern pop and rock adaptations. Some examples are listed as follows.

Art Song Tradition (classical music)

| Poet | Poem | Musician | Music |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goethe | Das Veilchen | Mozart | Das Veilchen (The Violet) |

| Ludwig Rellstab | Ständchen | Schubert | Ständchen (Serenade) |

| Shakespeare | O Mistress Mine | Theodore Chanler | O Mistress Mine |

| W. B. Yeats | The Secrets of the Old | Samuel Barber | The Secrets of the Old |

| Walt Whitman | One Thought Ever at the Fore | Ernst Bacon | One Thought Ever at the Fore |

| E. E. Cummings | The Mountains are Dancing | John Duke | The Mountains are Dancing |

Modern Rendition (contemporary music)

| Poet | Poem | Musician | Music |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edgar Ellen Poe | The Raven | Lou Reed | The Raven |

| Federico García Lorca | Pequeno Vals Vienés | Leonard Cohen | Take This Waltz |

| William Blake | The Chimney Sweepers | Allen Ginsberg | The Chimney Sweepers |

| Emily Dickinson | Hope Is The Thing With Feathers | Trailer Bride | Hope Is The Thing With Feathers |

| Alfred Tennyson | The Lady of Shalott | Loreena McKennitt | The Lady of Shalott |

| Rudyard Kipling | If | Joni Mitchell | If |

This project endeavors to unveil the enigmatic connections that lie beneath the surface of poetry and music, exploring uncharted territories within the interplay of author-reader relationships. It serves as a conduit for sharing not only creative and compositional revelations but also for fostering a dialogue between different genres and disciplines. By doing so, it sparks fresh perspectives on the realms of literary and artistic translation, uncovering hidden potentials and ushering in innovative avenues of expression.

Translation Process

The song adaptation titled “The Tulips” draws its inspiration from Eric Schlich's evocative flash fiction piece, “When You Are Old and I Am Gray,” which was published in Issue 59 of ASU's esteemed literary journal, Hayden's Ferry Review. This transformational journey exemplifies the synergy between poetic resonance and musical cadence, culminating in a song that amplifies the raw emotional beauty of the original prose. The upcoming sections intricately unravel the step-by-step evolution of this translation, shedding light on the organic interplay of poetic and musical elements, a fusion that impeccably enhances the profound sentiments embedded within Schlich's work.

The inspiration for this song stems from my literary translation of the original text from English to Mandarin Chinese.

I found in some of the original lines distinct musical qualities that are typical of lyrical poetry, such as rhymes, repetitions of words and phrases, and the direct expression of personal feelings.

[ASSONANCE] vase-grace-gray

Example Sentence 1:

dying over the lip of the VASE:

the tulips, their sloping GRACE.

慢慢凋谢于花瓶的边沿(yán):

郁金香,它们优雅的曲线(xiàn)。

title line: When You Are Old and I Am GRAY

an ending rhyme pattern based on the diphthong |ei|: GRAY – VASE – GRACE

The initial musical characteristic I explore is assonance. In the concluding sentence of the source text, it reads, “dying over the lip of the vase, the tulips, their sloping grace.” An observant ear would discern the interwoven vowel pairings such as “over” and “slope,” “lip” and “tulip,” and “vase” and “grace.” These pairings delicately mold the two clauses of the sentence into a harmonious rhyming couplet. Notably, the words “vase” and “grace” resound with the concluding word of the original title – "gray." This hints at a poetic symmetry rooted in the |ei| diphthong sound. This phonetic motif, originating from the title's word “gray,” finds its return in the words “vase” and “grace,” establishing a compelling resonance that mirrors the rhyming cadence.

[REPETITION]

Example Sentence 2:

Long ago, a tulip was just a tulip.

This is so long ago, it is a time I can barely remember, a time before you.

很久以前,郁金香只是郁金香而已。

那是很久以前,游离记忆之外,在你出现之前。

Example Sentence 3:

This is how something simple, something in this world, something that just is, takes on meaning.

这便是简单之事,世上之物,本真之貌,变得意义非凡的方式。

Another prominent musical attribute is the deliberate repetition of specific words and phrases. In the opening sentence, the term “tulip” emerges twice, accompanied by the repetition of “long ago” and “a time.” The subsequent sentence echoes the word “something” thrice. This repetition serves a purpose beyond mere linguistic recurrence – it guides us into a mental realm where the words transition from conveying distinct meanings to generating a heightened focus on their rhythmic sounds and cadences. As we encounter these reiterated words, our cognitive attention to their semantic content wanes, while our awareness of the melodic syllabic patterns intensifies.

This auditory transformation shifts the very nature of these words from conventional speech to a musical symphony. This psychological phenomenon, known as semantic satiation, demonstrates the gradual detachment of the words’ semantic significance, enabling the musical facets to wield a stronger emotional and physical influence over us.

The inherent musicality of the original text ignited my creative drive, propelling me to fashion these sentences into a dynamic verse-chorus song arrangement. Aiming to forge a fresh fusion between language and melody, I started an improvised exploration, strumming various chord progressions on my acoustic guitar. As each set of chords resonated, I carefully wove melodies that suit the flow of the chosen sentences. This process not only paid homage to the text's emotive cadence but also breathed new life into its essence, culminating in a harmonious marriage of words and sounds.

dying over the lip of the vase,

the tulips

you said how lovely they look, their sloping grace

as if the night has lost its way to the day

as if time has stopped for them to celebrate

as if they will stay here and never fade away

To shape the song's structure, I initially crafted a core ending rhyme scheme, interweaving words from the original text that feature the resonant diphthong [ei]. This diphthong, heralded by the final word in the title, "When You Are Old and I Am Gray," anchors an evolving pattern of musical rhyme. It harmoniously navigates through concluding phrases such as “way,” “page,” “weighed,” “table,” and “vase.” Ultimately, it crescendos to a fulfilling culmination in the word “grace,” akin to a musical piece that commences and concludes with the tonic, offering stability and a sense of closure, a melodic home.

In pursuit of constructing the main verse segment, a need emerged for additional rhyming sentences that culminate with words housing the diphthong [ei]. Thus, I penned three more sentences that echo the sentiment encapsulated within the original text's final sentence: “our time together cannot be weighed in the currency of bananas or books or even tulips.” These supplementary lines maintain the conversational cadence while deepening the narrator's assertion that the love shared transcends temporal constraints. Concurrently, each of these added sentences culminates in a word boasting the [ei] diphthong, enhancing the coherence of the Verse I section's rhyming schema.

CHORUS:

I wait for you in the dawning rays

when you are old and I am gray

VERSE I:

dying over the lip of the vase, the tulips

you said how lovely they look, their sloping grace

as if the night has lost its way to the day

as if time has stopped for them to celebrate

as if they will stay here and never fade away

VERSE II:

O so long ago,

It is a time I can barely remember

a time before you

All that I need to know

is you love this flower and I love you

when you are old and I am gray

The Verse II section serves as a vital link between the first occurrence of Verse I and its repetition. All the lines in Verse II are directly extracted from the original text. The first three lines condense Example Sentence 2, capturing the essence of “This is so long ago, it is a time I can barely remember, a time before you.” Lines 4 through 6 amalgamate elements from the original sentence (“–but really all that matters is you love this flower and I love you”) with the refrain (“when you are old and I am gray”). In doing so, Verse II enhances the overarching theme of love versus the passage of time and contributes to the song's structural dynamics.

Additionally, I incorporated the original title as a recurring refrain throughout the entire song. It appears at the conclusion of both the chorus and Verse II, reinforcing the central message of the original text: that the love shared between the couple grows stronger despite their advancing age and diminishing physical vigor.

When I adapted the original sentences into lyrics, my approach was always guided by the musical context. The words in a song hold a distinct role compared to those in prose or poetry. Lyrics thrive when complemented by the musical backdrop, whereas the latter often stands independently to convey the complete narrative, employing a combination of storytelling, imagery, and emotional resonance. Lyrics, rooted in a poem, may occasionally seem incomplete as they intentionally leave room for the musical arrangement to fill in the expressive gaps. This complementary relationship between lyrics and music results in a deeper semantic and structural unity within the song.

Progression 1. [Chorus; Verse I; Solo]

Cmaj7 - D6 - Asus2 - Asus2

Cmaj7 - D6 - E - E

Progression 2. [Verse II]

a half-step descending line cliché

E–D–#C–C–A–B–E–E

In crafting this song, I incorporated two distinct sets of chord progressions. The first progression contains eight bars and comprises the chords C major 7th, D 6th, A suspended 2nd, and E. This particular sequence finds its place in the Chorus section, the Verse I section, and the Solo section. The second eight-bar progression centers around the E chord and features a descending half-note bass line to guide its movement. This second progression comes to life in the Verse II section.

The rhythmic pattern in this song maintains a deliberate simplicity and consistency. To convey the chords, I opted for a right-hand finger-picking technique. The song adheres to a 4/4 time signature, featuring a continuous eighth-note progression in each bar. This rhythmic structure harks back to the characteristic style of 1960s and 1970s folk songs, reminiscent of tracks like The Beatles’ “Yesterday,” Paul Simon’s “Scarborough Fair,” and The Who’s “Behind Blue Eyes.” The choice of this eighth-note rhythmic pattern serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it aims to evoke a sense of nostalgia akin to the original speaker's voice in the source material. Secondly, it directs the listener's focus towards the vocal dynamics of the singer-storyteller, as opposed to the guitar accompaniment’s shifting rhythms.

Once the lyrics found their rightful places within the rhythmic structure dictated by the ebb and flow of chord progressions, I proceeded to craft the primary melodic lines. With my guitar, I played a specific chord progression on a continuous loop, simultaneously allowing the words to flow naturally from me as I hummed them in an improvised manner. I permitted various melodic lines to organically merge with the chord progression's natural cadence. I patiently awaited those ephemeral yet unforgettable moments when words and melodies harmoniously converged, capturing these spontaneous impulses and combinations in recorded form.

Subsequently, I reviewed these recordings, selecting those that evoked intense emotions, giving me goosebumps or even bringing tears to my eyes. I then revisited these chosen melodic lines, singing them aloud alongside my guitar to ensure each note achieved a more precise pitch, duration, and emphasis. These refined renditions were documented within computer music software soundtracks, where final editing and mixing took place.

Conclusion

In the realm of poetry, I’ve always perceived a profound poetic force within the silences that reside between words, following words, and lingering behind words. These silences possess a potency that rivals the words themselves, as they often serve as moments when readers actively engage in the artistic process. It's during these pauses that their thoughts stir, memories awaken, emotions are shared, and imaginations are ignited. When translating a poem into a song, it becomes imperative to faithfully represent and preserve these silences through thoughtful arrangements of rests, extended notes, and stress patterns.

I had the incredible opportunity to perform and refine this song through my participation in several events, including Thousand Languages’ 2022 Fall Spotlight, ASU’s 2023 Spring “Change the World” event, and Thousand Languages’ translation panel at the Northern Arizona Book Festival in April 2023. I hope that you have discovered something inspiring, resonating, and promising in my exploration of how a literary text can be translated into a song and how a song can unlock the emotional power of a poetic work. If you come across any errors or issues in my explanations, please don't hesitate to reach out to me. And if you share a similar interest or are eager to learn more about this poetry-music translation project, I warmly invite you to join us.

This project is run by TLP Intern Zhongxing Zeng

About Zhongxing

Zhongxing Zeng is a Ph.D. (Literature) student in the English Department at Arizona State University. His research interests include William Blake, English Romanticism, and English-Chinese Literary Translation. He is also a singer-songwriter with publications of original music on NetEase Music, Apple Music, and Spotify under the artist name 曾寅. (updated 2023)

This project was completed in Fall 2023.